One of the advantages of writing a short-story collection is that I can send my characters travelling to places that I have enjoyed visiting myself. One such location is a small town that we discovered while searching for a coffee shop during a cross-country driving trip several years ago. Fort Benton, which boasts of being ‘The birthplace of Montana’, is located on the Missouri River a little below the series of rapids that gave Great Falls its name. Because the river was not navigable beyond that point, the town became the place where the steamboats stopped and the stage coaches began.

Starting as a fur-trading post and later sold to the military, Fort Benton was where infamous trails such as the Whoop-up Trail to Alberta and the Fort Walsh Trail to Saskatchewan began. According to one of the plaques in the riverside park, the town in the early days was so wild that the U.S. Calvalry had to be called in if arrests had to be made.

Starting as a fur-trading post and later sold to the military, Fort Benton was where infamous trails such as the Whoop-up Trail to Alberta and the Fort Walsh Trail to Saskatchewan began. According to one of the plaques in the riverside park, the town in the early days was so wild that the U.S. Calvalry had to be called in if arrests had to be made.

With the advent of the North West Mounted Police in 1874, however, the whiskey trade was halted and an era of commercial interaction and cooperation between Canada and Fort Benton began. This historic connection is reflected in the three flagpoles that stand by the river, for the Canadian flag flies between the U.S. and the Montana State flags.

With the advent of the North West Mounted Police in 1874, however, the whiskey trade was halted and an era of commercial interaction and cooperation between Canada and Fort Benton began. This historic connection is reflected in the three flagpoles that stand by the river, for the Canadian flag flies between the U.S. and the Montana State flags.

In 1883, the completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad to Helena and the Canadian Pacific Railroad to Calgary caused a decline in business and ended Fort Benton’s importance as a prosperous commercial hub; however, there are still many fascinating sites to see that reflect the town’s history and its glory days. The Fort Benton Bridge, which was the first bridge to cross the Missouri River in Montana Territory, is the oldest steel truss bridge remaining in the state.

In 1883, the completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad to Helena and the Canadian Pacific Railroad to Calgary caused a decline in business and ended Fort Benton’s importance as a prosperous commercial hub; however, there are still many fascinating sites to see that reflect the town’s history and its glory days. The Fort Benton Bridge, which was the first bridge to cross the Missouri River in Montana Territory, is the oldest steel truss bridge remaining in the state.  Although a new traffic bridge was built in 1963, the old bridge is accessible as a walking bridge and provides lovely views of the river and surrounding hills. When I strolled out and watched the powerful Missouri churning past the metal plates that sheathed the concrete piers below the bridge, I realized it was the perfect location to begin a mystery story.

Although a new traffic bridge was built in 1963, the old bridge is accessible as a walking bridge and provides lovely views of the river and surrounding hills. When I strolled out and watched the powerful Missouri churning past the metal plates that sheathed the concrete piers below the bridge, I realized it was the perfect location to begin a mystery story.

Another striking historical landmark in Fort Benton is the Grand Union Hotel, built in 1882. Although the hotel failed when the town’s fortunes declined, a multi-million-dollar project in the nineties restored the hotel to its former elegance, and now it provides a delightful lodging and dining experience for visitors to the town. Fine dining, old-world atmosphere, and a saloon providing beer on tap with highly original names! My husband and I thoroughly enjoyed our stay there, and I resolved on the spot that one of my story characters would have to stay there at some point in the future.

Another striking historical landmark in Fort Benton is the Grand Union Hotel, built in 1882. Although the hotel failed when the town’s fortunes declined, a multi-million-dollar project in the nineties restored the hotel to its former elegance, and now it provides a delightful lodging and dining experience for visitors to the town. Fine dining, old-world atmosphere, and a saloon providing beer on tap with highly original names! My husband and I thoroughly enjoyed our stay there, and I resolved on the spot that one of my story characters would have to stay there at some point in the future.

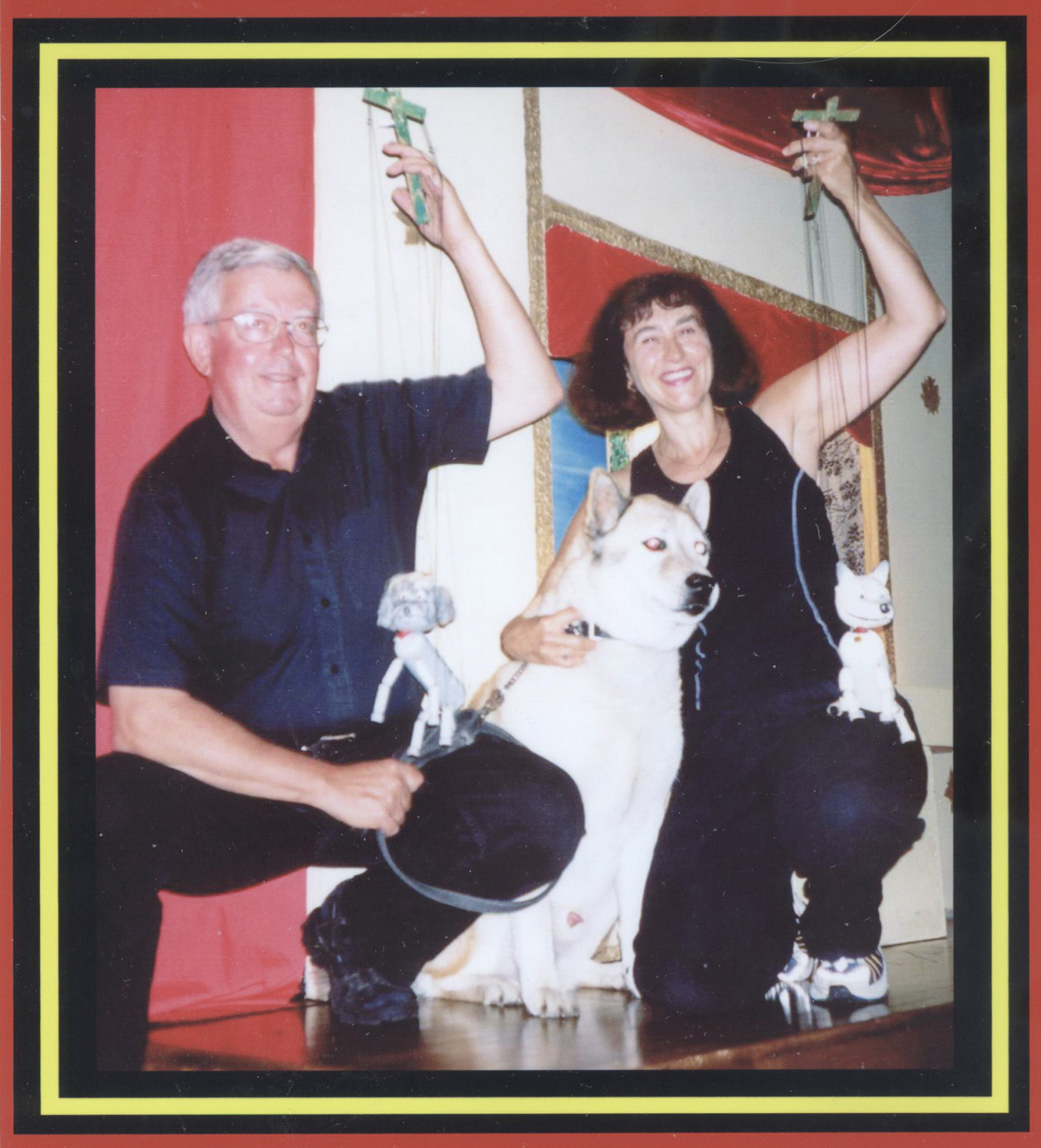

The thing that most deeply touched my heart, though, when we first visited the town, was the statue of a dog that stands outside the Grand Union Hotel. Our dog, Max, had died shortly before we began our trip, so the Montana memorial was particularly moving for me. The statue is of a dog called Shep, whose sad story goes back to 1936 when his master died and the body was sent back east at the request of his family. The faithful dog kept vigil at the railway station, continuing to watch for his master until the day he died. Shep was buried on the hillside overlooking the railway station and a small cairn marks the spot, alongside the original Shep memorial.

The thing that most deeply touched my heart, though, when we first visited the town, was the statue of a dog that stands outside the Grand Union Hotel. Our dog, Max, had died shortly before we began our trip, so the Montana memorial was particularly moving for me. The statue is of a dog called Shep, whose sad story goes back to 1936 when his master died and the body was sent back east at the request of his family. The faithful dog kept vigil at the railway station, continuing to watch for his master until the day he died. Shep was buried on the hillside overlooking the railway station and a small cairn marks the spot, alongside the original Shep memorial.

The statue by the hotel is a bronze sculpture surrounded by bricks that people can buy to commemorate their own pets. Naturally, we bought a brick to commemorate Max, and on a subsequent trip to Montana, we returned to see it in place. So if you ever visit Fort Benton, be sure to look for the brick that bears the name, Max, the Ho Hum Husky.

The statue by the hotel is a bronze sculpture surrounded by bricks that people can buy to commemorate their own pets. Naturally, we bought a brick to commemorate Max, and on a subsequent trip to Montana, we returned to see it in place. So if you ever visit Fort Benton, be sure to look for the brick that bears the name, Max, the Ho Hum Husky.

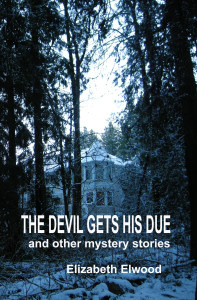

The Shep statue was not the only moving tribute to dogs in the town of Fort Benton. The military park adjacent to the fort has a section devoted to service dogs, and predictably, one of the plaques is dedicated to a Shep who served in Vietnam. Naturally, having visited the two Shep memorials and having read the touching dedication to service dogs in the military park, it was inevitable that the final story in my latest book would be a novella set in Fort Benton and developed around a series of incidents related to dogs. Now that The Devil Gets his Due and Other Mystery Stories is out, I hope readers will enjoy their literary visit to this charming town as much as I enjoyed our stays there.

The Shep statue was not the only moving tribute to dogs in the town of Fort Benton. The military park adjacent to the fort has a section devoted to service dogs, and predictably, one of the plaques is dedicated to a Shep who served in Vietnam. Naturally, having visited the two Shep memorials and having read the touching dedication to service dogs in the military park, it was inevitable that the final story in my latest book would be a novella set in Fort Benton and developed around a series of incidents related to dogs. Now that The Devil Gets his Due and Other Mystery Stories is out, I hope readers will enjoy their literary visit to this charming town as much as I enjoyed our stays there.

Oh, and by the way, Fort Benton did have that coffee shop we were looking for, and it was a delightful one too!

Oh, and by the way, Fort Benton did have that coffee shop we were looking for, and it was a delightful one too!

Now available on Amazon

[box]

EXCERPT: The footbridge that crosses the Missouri River at Fort Benton is the most historically significant bridge in Montana. Certainly, it is one of the oldest, built in 1888, a year before the Territory became a State and the first bridge to ford the Missouri in Montana. For seventy-five years, the steel-truss bridge carried traffic—horses, carts and wagons in the early days, and later motor vehicles—but in 1963, a new bridge was built a quarter-mile upstream, and the old steel bridge was closed. The striking quartet of trapezoidal trusses connecting to the east bank remains intact; however, the original swing span that was constructed to allow the passage of steamboats was replaced when the centre pier was washed out in a flood in 1908. Today, the west bank connects to the original structure by a long camelback span, supported, like the original trusses, by concrete piers sheathed in metal plates. The old bridge now serves as a pedestrian feature of the river park, although it can only be accessed from the west side, as the cottonwood-laden east bank is privately owned. So while the traffic in and out of Fort Benton motors across the Chouteau County Memorial Bridge by the Grand Union Hotel, tourists strolling the river path can walk out over the old bridge and look back towards the unique little town that constitutes the birthplace of Montana.

However, on a Saturday morning in September, tourists are a rare commodity, and the locals, long used to the black metal span yawning over their river, rarely deem it worth the crossing, knowing that they simply have to return again. Walkers and joggers stick to the river path and feel no temptation to turn onto the concrete walkway that leads to the bridge. But children are another matter, and the young Mason boys and their friend, Rory O’Mara, considered it an adventure to walk out along the wooden planking and stare down at the swirling waters below.

As they reached the point where the camelback truss ended and the trio of Baltimore trusses began, the boys turned back to see one of their schoolmates walking her dog along the river path. The German shepherd was bounding ahead, and as it came to the bridge, Jack Mason whistled and yelled out, “Hey, Shep! Here boy!” As an afterthought, he waved to the girl and added, “Sally, come join us.”

Shep darted onto the planked walkway. Sally waved back and followed the dog onto the bridge. She was only part way along the camelback span by the time the dog reached the boys. Ralph Mason gave the dog a perfunctory pat and then leaned out over the railing. He liked to see the powerful water surging up and curling around the metal plates.

Jack and Rory started to play with Shep, but Ralph remained mesmerized by the water below the bridge. Something that looked like a sack seemed to be bobbing against the concrete pier.

As Sally reached the end of the first span, Shep abandoned Jack and raced back to meet her. Rory turned to see what had transfixed his friend’s brother.

“There’s a sack down there,” said Ralph. “It’s caught on the pier. It’s full of some stuff, and there’s bits of cloth attached to the back of it.”

“No way,” said Rory. “A sack wouldn’t float.” He moved to the railing and stared down into the water.

“Jeez, you moron,” he said. “That’s not a sack. It’s got legs. That’s a body down there.”

Jack abandoned Shep and came to the railing.

As the boys stared downwards, the body lifted, and an expanse of tan cowhide rose and subsided, its tattooed insignia of interlocking antlers hovering momentarily in view before it glided back under the slate grey water.

“Holy moly, that’s The Colonel!” said Ralph.

Jack’s eyes bulged and his face went white. Then he gasped as the force of the current rolled the torso against the pier. He felt suddenly sick. He reeled away from the railing and threw up.

“What are you guys staring at?”

Sally’s voice behind him made Ralph look round. She and Shep had reached the centre span.

“We gotta get the sheriff,” said Rory. “There’s a body down there.”

“No,” breathed Sally. “Are you serious?”

She moved towards the railing.

Ralph stopped her. Even at the age of ten, cowboy-country gallantry was ingrained in his psyche, and he had already seen the effect of the corpse on his older brother.

“Don’t look,” he said firmly. “He doesn’t have a head.”[/box]

The Morton family suffered a tragedy when their daughter was the victim of a serial killer. Two decades later members of the family gather at the Marshlands Hunting Lodge, where unbeknown to them, two people are present who are connected to the earlier crime. A storm causes landslides that render the access road impassable, and before long, another murder takes place.

The Morton family suffered a tragedy when their daughter was the victim of a serial killer. Two decades later members of the family gather at the Marshlands Hunting Lodge, where unbeknown to them, two people are present who are connected to the earlier crime. A storm causes landslides that render the access road impassable, and before long, another murder takes place.